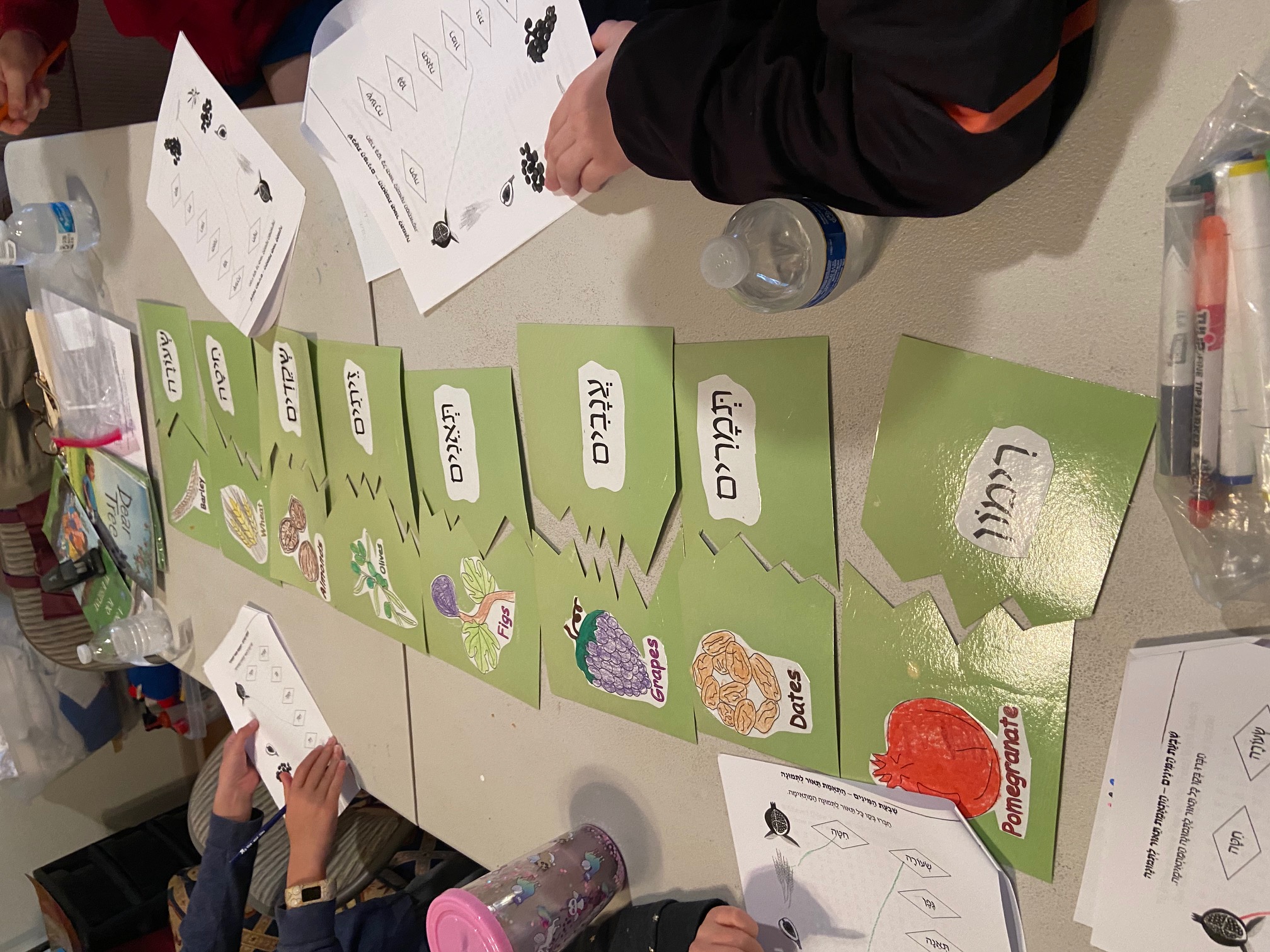

| Tu Be Shevat Parasha from Rabbi Peter Tarlow. Many decades ago when I was a graduate student a new holiday was invented: Earth Day. Considering that Jews had been celebrating “earth day” for thousands of years I found it a bit odd that the media and university intellectuals saw this holiday as new and innovative. Our Biblical tradition provides great respect for the land and all that it contains. On Thursday, just as we have done for thousands of years before the birth of “Earth day” we once again celebrated Tu b’Shvat: The New Year of the Trees and our relationship to nature. Traditionally, this holiday is the day that trees begin to bloom in the land of Israel, and each year we plant thousands of saplings throughout the land. Tu b’Shvat is a more than the mere planting of trees, it is also a time to stop and contemplate our relationship to G-d through nature. From its very inception Judaism has incorporated the ideas of ecology into its religious tradition. Thousands of years before the Western world rediscover the importance of ecology Tu b’Shvat’s taught us that there is a relationship between the natural world and the spiritual. On Tu b’Shvat we celebrate not only the importance of nature but also through the “divine tree of life” (the Torah) we creatively symbolize the unity of matter and energy, of the spiritual and the material.This holiday gives life to the psalmist’s words: “l’Adoshem ha’aretz umloah, tevel v’yoshvei-va/The earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof, the world and all who dwell with in it”. (Psalm 24:1).This week’s Torah portion also reinforces our relationship to G-d and nature. This week’s portion is B’Shalach (Exodus 13:17-17:16). Dealing with Israel’s liberation from Egypt, and the successful crossing of the Red Sea (Sea of Reeds), it would appear that this section has nothing to do with Tu b’Shvat. Yet this section of contrasts serves to remind us of our dependency not only on G-d but also on the world that G-d has given us. Coming from the banks of the Nile river, having crossed a sea and now in the midst of the desert, the flight from Egypt has left an eternal mark on the Jewish people. To be in the Sinai desert, a place without trees, Jews came to understand that trees are life and clean potable water is a blessing from Heaven.This is the first parashah to take us on the long 40-year zigzag journey through the desert. Along the way, we learn that this was to be a journey of opposites: where the ecstasy of revelation confronted the desert’s tedious boredom, where the wonder of manna would be contrasted to the consistency of thirst, and where the vision of Israel was contrasted to the starkness of the Sinai Peninsula. From this week’s section until the end of the Deuteronomy, we, the readers, wonder if G-d’s is not teaching us in a roundabout way that to be a people we cannot depend on miracles but rather only on our inner spiritual fortitude, that to ignore the land, is to put oneself in peril. The Sinai experience taught us that knowledge, like freedom, is liberating, and freedom is not squandering the gifts of nature but protecting and persevering nature for future generations. Happy Tu b’Shvat! |

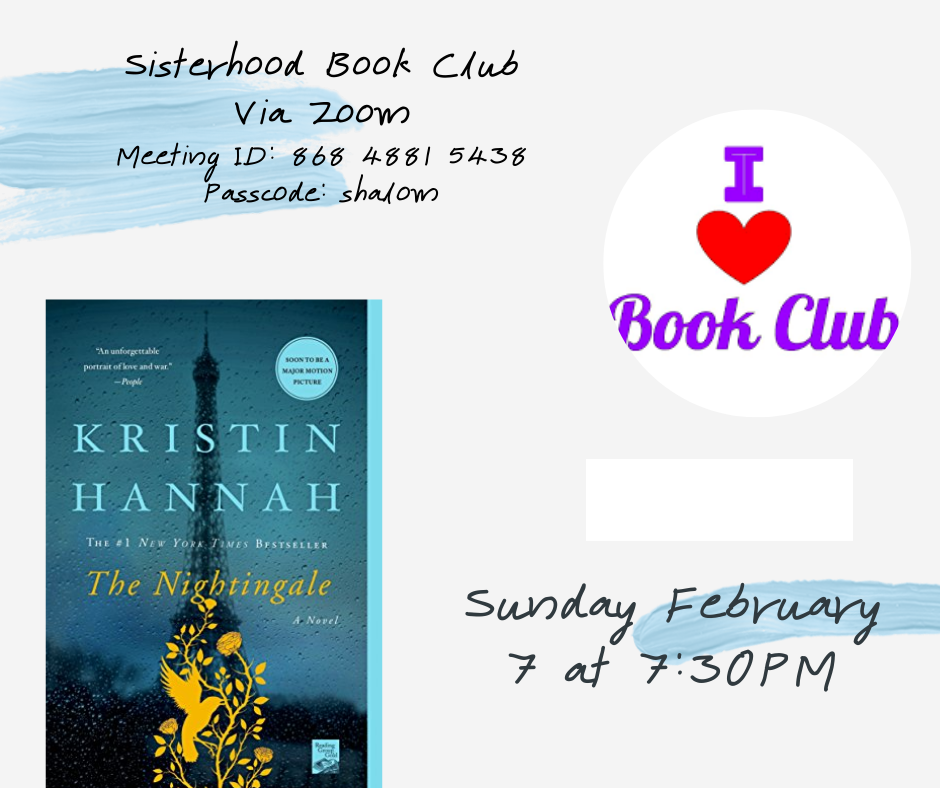

Sisterhood Book Club:https://us02web.zoom.us/j/86848815438?pwd=cHE0ZEM2NXpEZTEvQ2M1V3hBQzBUZz09

Sisterhood Book Club:https://us02web.zoom.us/j/86848815438?pwd=cHE0ZEM2NXpEZTEvQ2M1V3hBQzBUZz09

Austin Jewish War Vets Post 757 is very interested in gaining new members. We meet monthly on Zoom and would like to invite all of your veterans to our meetings. They are welcome to sit-in as guests.To join in our next JWV Zoom meeting pleasecontact: Charlie Rosenblum Commander, Post 757Jewish War Veterans of the United StatesAustin, Texasjwvaustin@gmail.com (254) 368-5715

Austin Jewish War Vets Post 757 is very interested in gaining new members. We meet monthly on Zoom and would like to invite all of your veterans to our meetings. They are welcome to sit-in as guests.To join in our next JWV Zoom meeting pleasecontact: Charlie Rosenblum Commander, Post 757Jewish War Veterans of the United StatesAustin, Texasjwvaustin@gmail.com (254) 368-5715